Her Masquerade (catalogue)

Mary Birmingham, curator

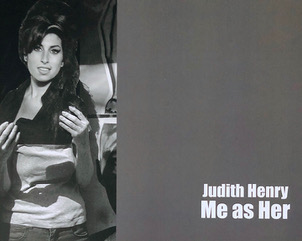

Me as Her, Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, Summit, NJ

2016

Judith Henry has spent more than forty years secretly observing, listening to, photographing, filming and recording strangers in public places, while remaining largely invisible to her subjects. Who I Saw in New York (circa 1970-2000) is a huge archive of the black and white snapshots she took of pedestrians. Her “Overheard” book series published by Universe/Rizzoli (2000-2002) pairs photographs with texts excerpted from eavesdropped conversations, and includes the well-known, Overheard at the Museum. Several years ago, she surreptitiously photographed people as they posed for snapshots on a concrete barrier beside the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

In several recent bodies of work, however, Henry has evolved from an invisible observer into an active, though hidden participant. Disguising herself with different types of handmade masks, she inserts herself into each photograph and, in a sense, becomes the subject—but not entirely as herself. In the series, Girls, Girls, Girls, she restaged high school yearbook photos and posed behind hand-drawn masks of young women to create portraits of shared identity. In The Artist Is Hiding she has appropriated an artistic, rather than a personal identity. For this series Henry holds mixed-media masks and poses in front of paintings that, like the masks, echo or quote various movements and styles of abstract art. Me as Her continues Henry’s practice of hiding within her work and masquerading behind a façade or false identity. Characteristically, in all of these works her personal identity is revealed only through the inclusion of her hands, which is an important signature aspect of each piece.

In Me as Her, she creates black and white portraits of famous deceased women in scenes from their daily lives. Not quite candid snapshots, these photographs record momentary interruptions as the women acknowledge or even pose for the camera. They are arresting images that upon further scrutiny seem a bit unsettling, as we begin to notice that the faces are somewhat disjointed from their bodies and articles of clothing don’t always match. The subjects’ hands feature prominently in all of the portraits, ultimately revealing the fact that these are staged photographs in which a woman holding a mask in front of her face is posing as each of the subjects. While her face remains hidden in all of the portraits, the inclusion of her hands provides a clue to her identity as an older woman.

As she has aged and retrospectively assessed her own accomplishments and identity, the artist began thinking about accomplished women she admired who had died. After living most of her adult life in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, Henry moved to Williamsburg, Brooklyn in 2006. Having discovered this hip, young neighborhood later in life she wondered, “What if these women came to Williamsburg like I did?” Sourcing black and white images from the Internet, she made life-size photographic masks of these significant women and posed behind their faces in neighborhood spots where she envisioned them. While the individual masks represent specific women, as a group they also characterize a broad spectrum of female identity with their diversity of age, race, religion, and vocation. Since all of them are deceased, Henry became their surrogate, borrowing their identities and taking them to places they most likely never visited—all within a one-mile radius of her home.

Georgia O’Keeffe stands in Henry’s own garden, Virginia Woolf sits reading with head in hand at a quiet café table, and Anna May Wong lights a cigarette while perched at a marble-topped bar. It is to Henry’s credit that she integrates the women so seamlessly into the Williamsburg scene of today. With her slightly ironic placements— Susan Sontag standing beside graffiti that looks like a thought bubble, Jean Stapleton beaming in a Laundromat—she is clearly having fun with this project, and for the viewer, the humor is infectious. In the portraits of Amy Winehouse and Selena, who died tragically, the contrast between their youthful faces and the artist’s aging hands is especially poignant. Henry’s photographs render these women forever young, frozen in a place and time that never really existed for them.

At times, each of us has probably fantasized about being someone else. Judith Henry’s haunting photographs enact her fantasies and invite us to witness the power of her masquerade.

back to CV